An intro to the melted, gooey mind of a post-finals PhD student

In the days preceding my game theory final, I was quarantined in my Cambridge apartment. The heat was on and pages of yellow legal paper decorated with inky matrices and tree diagrams ruled my kitchen counters. Swaddled in some convex combination of polar fleece and section notes, I would only leave my warm fortress to (1) throw $4 at an increasingly hard-to-please chai tea habit, and (2) play and train for my sport of choice–that is, ultimate frisbee.

When I would return from ultimate, residual thoughts about the game lingered at the edges of my legal pads. The combination of studying for my exam and ultimate exposure in the throes of winter madness led me to the inevitable: reframing game theory concepts as they apply to aspects of ultimate! While I didn’t have the time to parse out examples of “Ultimate” Game Theory back in Cambridge, I’m on winter break in San Francisco now… which means I am still wearing lots of fleece, and I have time to tease out all the kitschy alt-sport applications of game theory that my heart desires.

To discuss game theoretic concepts in this context, I build out two games that are based in the ultimate frisbee universe.1

- First, I use The “call lines” Game to discuss some popular, well-known concepts – namely, the prisoner’s dilemma and pure Nash equilibrium. I also use this framework to talk about repeated games and subgame perfect equilibrium. In adding the concepts of offense and defense, I refine the game so that it is no longer symmetric, and provide an example of how to solve for mixed Nash equilibrium.

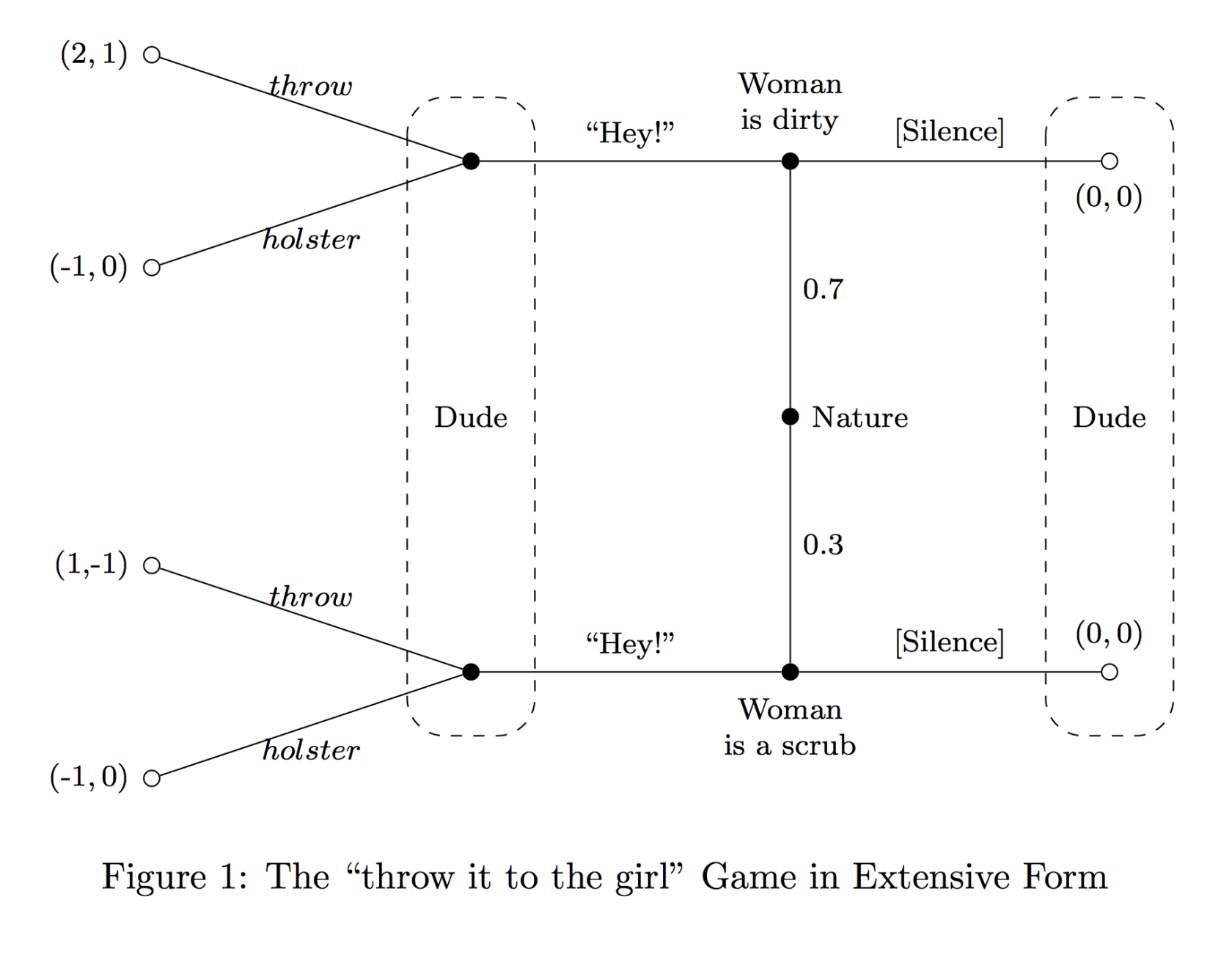

- The second game I herein created is The “throw it to the girl” Game. This game is much more complex and interesting than the former – it is a dynamic signaling game with imperfect information that allows me to illustrate how to solve for perfect bayesian equilibrium. The “throw it to the girl” Game allows us to model one kind of dynamic that can pop up in the social context of co-ed sports.

Game 1: The “call lines” Game

a. The Game Set-up

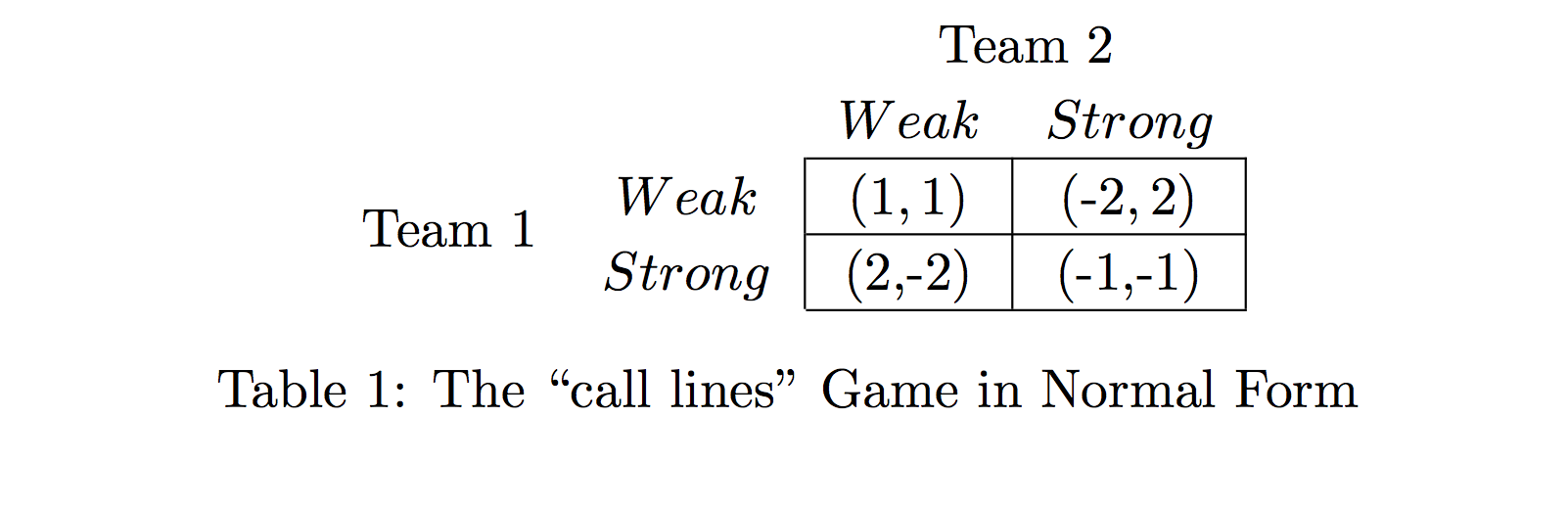

First things first, I present a simple game based on “calling lines” during an ultimate frisbee game. Ultimate is played with two teams. Each team needs to put 7 people “on the line” to play any given point. However, teams themselves consist of more than 7 people since otherwise those 7 people would probably not be super into playing this sport. (People need some rest!) In my set-up, I assume there are two teams, 1 and 2, that are identical and each always has two lines to choose from: a strong line and a weak line. The payoffs are determined by strategies employed rather than the identity of those teams employing them. In effect, the normal form of this game is a 2x2 symmetric matrix. (This is 2x2 since there are two players–team 1 and team 2–as well as two choices of lines–weak and strong.)

In order to determine the payoffs in this matrix, I need to make assumptions about the team outcomes. In expectation (which is how payoffs in a normal form matrix are presented – as expected Bernoulli utility), weak lines lose to strong lines and the same type of lines win or lose to one another with equal probability. A team gets +3/-3 for winning/losing a point. (If two types of the same type play, they receive 0 in expectation since the probability of a win is 0.5.)

Moreover, I assume that teams do not want to overuse their strong lines. I.e., teams do not want to wear out their best players for fear of fatigue or injury. Therefore, teams also receive payoffs of +1/-1 for playing a weak/strong line. Given these simple and linear assumptions,2 the following represents the normal form game for “call lines”:

b. Prisoner’s Dilemma Form & Solving for Pure Nash Equilibrium

The normal form of the “call lines” game might look very familiar. While conceptually different, it is mathematically identical to everyone’s favorite simple non-cooperative game: the prisoner’s dilemma! Note that the prisoner’s dilemma has infinite representations with respect to the specific payoffs. The overarching requirement is that the game is symmetric across the two players and that the following strict ranking of payoffs holds:3

[the payoff to a player who "defects" (plays a strong line) while the other "cooperates" (plays a weak line)] >

[the payoff to a player who "cooperates" (plays a weak line) while the other "cooperates" (plays a weak line)] >

[the payoff to a player who "defects" (plays a strong line) while the other "defects" (plays a strong line)] >

[the payoff to a player who "cooperates" (plays a weak line) while the other "defects" (plays a strong line)]

In table 1 we can see this holds since . I could replace these payoffs in the normal form matrix with any set that maintains the same strict inequality and the game would remain a prisoner’s dilemma.

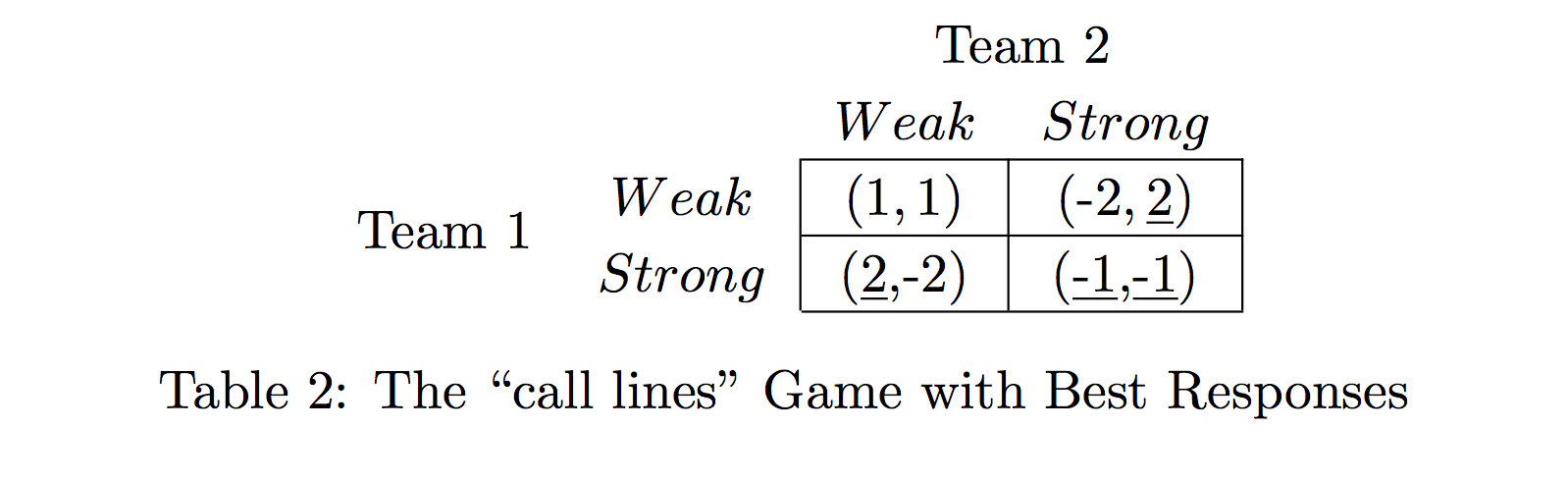

In the prisoner’s dilemma context, the relevant solution concept is the well-known concept of Nash equilibrium. In Nash equilibrium, no agent (team in this case) has an incentive to deviate if the agent knows the other’s strategy. In order to solve for Nash equilibrium, I underline the best responses of both teams to each other’s strategies:4

Since both payoffs in the box of the matrix are underlined, it is evident that neither team has an incentive to deviate from the strong strategy given that the other team is playing strong. Thus, strong-strong is the sole pure Nash equilibrium in the “call lines” game. However, note that the weak-weak strategy, which yields payoffs , while not Nash, is pareto optimal (no payoff duo gives both players a higher payoff) and, accordingly, pareto dominates . As Prof Maskin lecture slides wisely say, this “illustrates the tension between efficiency and individual maximization.”

c. Repeated Game Prisoner’s Dilemma & Solving for Subgame Perfect Equilibrium

While the original set-up of this game was in a static context, I can also render “call lines” a repeated game and end up with a different solution concept than the traditional Nash equilibrium previously described. Let’s assume that the same normal form game shown in Table 1 will be played infinitely – this generates an “iterated prisoner’s dilemma.” In this context, I use a solution concept known as subgame perfect equilibrium. Given repetition and recall of previous outcomes/actions, teams now have the opportunity to penalize each other for previous decisions. In the “call lines” context, I investigate the following strategy: play a weak line until someone plays a strong line (play strong from then on). This is also called a “grim trigger strategy,” which alters the choice of lines if someone chooses to deviate from cooperation (playing weak lines). This strategy, therefore, incentives cooperation since otherwise the players punish one another by forcing reduced payoffs for the rest of the infinitely repeated game.

This strategy yields efficiency in subgame perfect equilibrium – a point I show below. Imagine teams have discount factors, meaning they discount future utility flows from points played. The following break-down illustrates how the “grim trigger strategy” is a subgame perfect equilibrium (given some condition on the discount factor):

Thus, if the discount factor is greater than one-third, the grim trigger strategy is a subgame perfect equilibrium for the “call lines” game. However, note that if the number of repetitions of the game is finite and known to both teams, then (by backwards induction) the two players will play strong lines in every period. Therefore, the solution concept is the same as in the static context if the repetition is finite and known, but can diverge if the repetition is infinite and the discount factor meets some requirement.5

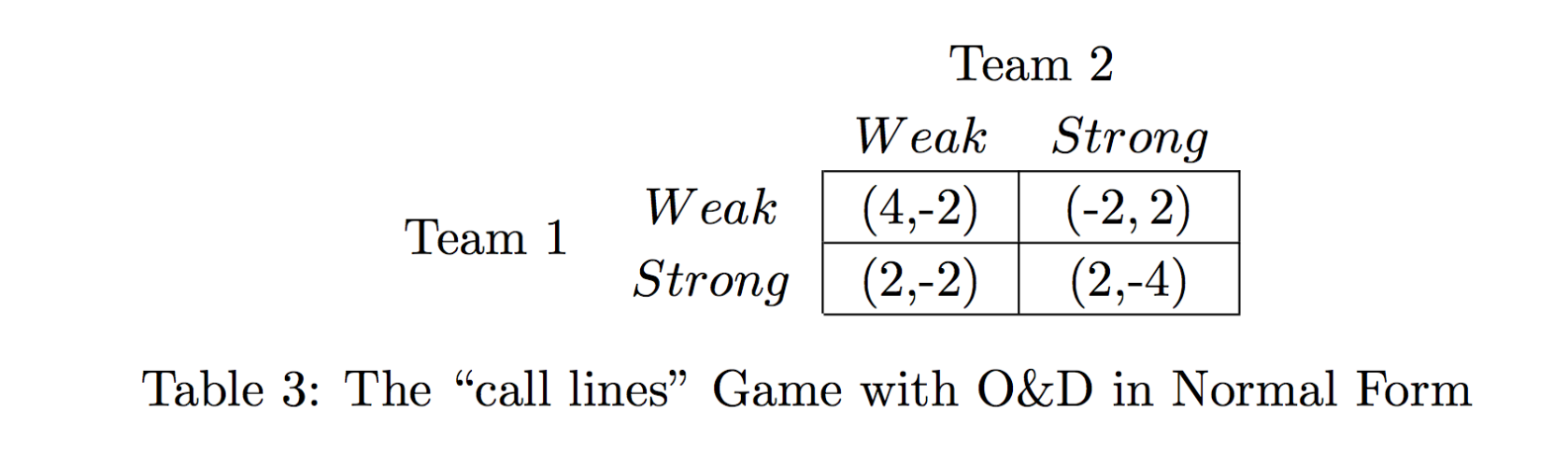

d. Adding Offense and Defense & Solving for Mixed Nash Equilibrium

I now refine the “call lines” game by adding the concepts of offense and defense. This addition will change the payoffs in the normal form matrix. Assume that team 1 is on offense and team 2 is on defense. When a team starts a point on offense (meaning the other team pulls the disc down field to them – a kick-off in football), they have an advantage for scoring. Assume accordingly that a weak offense will beat a weak defense and a strong offense will beat a strong defense. Therefore, the only offense that loses in a match-up is a weak offense against a strong defense. Maintaining the same +3/-3 for winning/losing a point and the same +1/-1 for strong/weak lines, the normal form game with player 1 on offense is as follows:

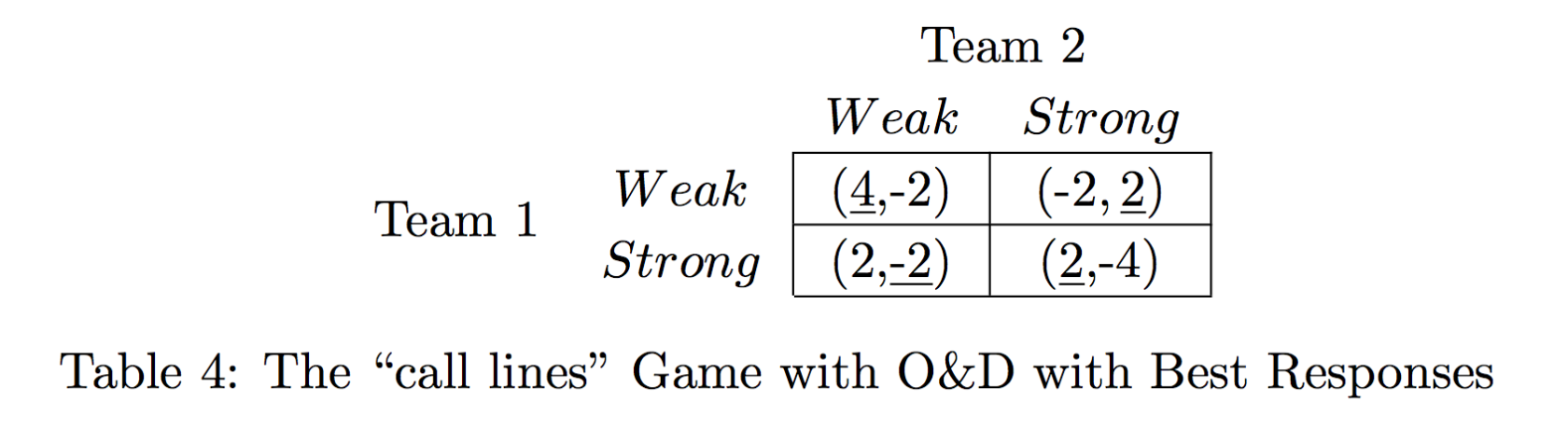

Given this change, the game is no longer symmetric. It is no longer a prisoner’s dilemma, and moreover, there is no longer a pure Nash equilibrium. This can be illustrated with the best responses marked below (i.e., there is no box with both payoffs underlined):

While there is no pure Nash equilibrium, we know that all finite games have at least one Nash equilibrium (theorem of existence of Nash equilibrium). Therefore, there must be some mixed Nash equilibrium. Mixed Nash equilibrium is made up of mixed strategies, which are those by which a team plays its available pure strategies (play a weak line, play a strong line) with certain probabilities. In solving for mixed Nash, we consider three possibilities (only team 1 uses a mixed strategy, only team 2 uses a mixed strategy, both use mixed strategies) and make use of the indifference condition as follows:

There is therefore one single mixed Nash equilibrium in which team 1 plays a weak line with probability 2/3 (and so a strong line with probability 1/3) and team 2 plays a weak line with probability 1/3 (and so a strong line with probability 2/3).

e. Recap of “calling lines”

In sum, we have used the original and refined “call lines” set-ups and their corresponding normal forms in order to discuss the prisoner’s dilemma, pure Nash equilibrium, repeated games, subgame perfect equilibrium, and mixed Nash equilibrium. In moving to a more complex and interesting set-up, I now transition to the “throw it to the girl” game.

Game 2: The “throw it to the girl” Game

a. The Game Set-up

Ultimate is played in a myriad of circumstances. The most casual form of ultimate frisbee is pick-up–that is, a group of people who get together to play who often don’t know each other. Pick-up is often mixed gender, meaning men and women are playing together, which while empowering and fun can often lead to some noticeable gender dynamics. For instance, playing pick-up in a mixed gender setting can lead to women being looked off" by male players.6 In other words, men sometimes do not throw to open women…which can lead to the classic “throw it to the girl!” remark from the sideline as a woman appears open upfield but the dude with the disc chooses to holster the throw instead. The reasons for this trend (preference for bigger, more dramatic plays in the form of hucks to big dudes, implicit bias, etc.) is not the focus of this discussion…rather, it suffices to note that, yeah, this is a dynamic.

In my own personal experience as a female pickup player, I’ve found that calling for the disc when open is a solid way to signal that I am more experienced or confident and that men shouldn’t hesitate to throw to me. In learning about dynamic signaling games in game theory, I quickly realized that this calling/throwing situation could easily be melded into game theoretic form.

Consider the moment when a male player with a disc is looking upfield for a throw. Assume there is an open female cutter upfield. In this moment, the female cutter (player 1 to us) has a choice: she can (1) call for the disc, signaling that she wants to be thrown to, or (2) remain silent and again not be thrown to.

This set-up is a two-player dynamic signaling game. While conceptually distinct, note that this game is identical to the well-known “gift game”! Player 1 has two types: she is either (1) dirty, or (2) a scrub.7 In this world, we are assuming that a dirty woman is better than the average male cutter on the pick-up team, while a scrub woman is worse than the average male cutter on the team. We assume that with probability 0.7 nature makes the woman dirty and with probability 0.3 nature makes her a scrub.8

Once the cutter has chosen to yell out or not, the dude with the disc (player 2) has a choice. Player 2 only has one type. He has no choice if the woman is silent since he will unambiguously not throw to her, but if she calls out, he can choose to throw to her or holster (not throw to her).

- If the woman is silent, the payoffs to both players are 0 regardless of player 1 type since no one gains from this and both players continue functioning at the status quo.

- If the woman calls out, the payoffs are different depending on her type:

- Let’s say she is dirty:

- If the dude throws to her, she gains 2 since she is happy she was thrown to and she played the disc well; the dude in this case is happy since she played the disc better than the average male cutter would have and gets a payoff of 1.

- If the dude does not throw to her, then she gets a payoff of -1. (This assumes, based on personal and shared experience, that women feel more ignored or disrespected when looked off after being openly vocal than after being silent.) Meanwhile, the dude in this case goes on with the status quo and gets a payoff of 0.

- Let’s say she is a scrub:

- If the dude throws to her, she gains 1 since she is happy she was thrown to. (But she doesn’t gain as much as the dirty woman since she’s not as dope at frisbee. I am assuming that people gain more utility from playing when they are dirty.) The dude, in this case, is unhappy since she doesn’t play the disc as well as the average male cutter so he gets payoff of -1.

- If the dude does not throw to her, she again gets a payoff of -1 and he again gets a payoff of 0. (We are assuming that dirty women and scrubs receive the same payoffs when ignored, but differ in payoffs when they get to play the disc.)

- Let’s say she is dirty:

Given these above assumptions for payoffs and dynamics, I used the TikZ package in LaTeX to build out an extensive form of this game.9 See figure 1 for the extensive form of this game:

b. Solving for Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium

In the context of such dynamic games with incomplete information, the equilibrium concept of interest is perfect bayesian equilibrium (a refinement of bayesian nash equilibrium and subgame perfect equilibrium).

In order to solve for perfect bayesian equilibrium (PBE from here on), I must investigate all possible strategies for our women in the pick-up game. Since we have two types of women (dirty players/scrubs) as well as two possible actions (call out/be silent), there are four possible strategies. Two of these are what we call “separating strategies” in which the two types choose different actions:

- dirty player is silent/scrub calls (Figure 2)

- dirty player calls/scrub is silent (Figure 3)

The other two are called “pooling strategies” in which both types choose the same action:

- dirty player is silent/scrub is silent (Figure 4)

- dirty player calls/scrub calls (Figure 5)

For each of the woman’s four possible strategies, I then determine the beliefs and accordingly the optimal response of the dude with the disc. Given that optimal response, I check to see if either of our types of women would like to deviate. If not, then we have a perfect bayesian equilibrium. I will now go through this systematically for the four strategies.

The above illustrates the separating equilibrium strategy in which the dirty player is silent and the scrub calls for the disc. (These actions for the two types of women are illustrated in red.) In a separating equilibrium, the action of player 1 signals the type, meaning that if the dude hears a “hey,” he knows she a scrub. The dude’s strategy (recall he only gets to make a choice when there has been a call for the disc) is then to holster the throw since . (Thus holster being highlighted in red in the left information set.) Note that given that optimal response from the dude, the scrub female player could improve her payoff by remaining silent instead since . In effect, this is not a PBE.

The next strategy we consider is that in which a dirty player calls for the disc and a scrub remains silent. In this separating case, the dude knows that if he hears a “hey,” the woman is dirty. So, the dude’s strategy is to throw since . (Throw is highlighted in red in the left information set.) Given this optimal response from the dude, the scrub female player could improve her payoff by deviating from silence to calling since . In effect, this is not a PBE.

The above figure illustrates the total silence strategy. In such a pooling equilibrium, the dude’s beliefs when hearing a disc called for can be arbitrary since hearing a “hey!” occurs with 0 probability and therefore bayes’ rule doesn’t apply in this context. In effect, if the dude’s beliefs as to the woman’s type are adequately pessimistic (believes with more than 50% certainty that she’s a scrub), then his strategy is to holster the throw (holster highlighted in left information set). (So, diagram is drawn for adequately pessimistic beliefs on the part of the dude.) Regardless of the probabilities determined by nature (0.7 and 0.3), neither player can improve by deviating since is inferior to . Therefore, this is a PBE.

The last strategy to look into is the all call strategy. In this pooling equilibrium, the dude’s beliefs as to the woman’s type are based on the nature a priori probabilities. The payoff from throwing is thus and the payoff from holstering is . Since , the optimal response for the dude is to throw (as marked by the red). Since and , neither type of woman wants to deviate from the prescribed strategy. In effect, this is a PBE.

c. Refining the Set of Perfect Bayesian Equilibria

In summary, there are two PBEs for this “throw it to the girl” game: the total silence and all call strategies. However, note that the total silence strategy is not Pareto efficient while the all call strategy is. I.e., the expected payoffs of 1.7 for the woman and 0.4 for the dude (all call strategy) are larger than 0 payoffs for both (total silence strategy). Moreover, the total silence strategy fails “the intuitive criterion,” a refinement of the set of equilibria proposed by Cho and Kreps (1987). The concept of this requirement is to restrict the set of equilibria to those with “reasonable” off-equilibrium beliefs. This allows me (as the creator of the model) to choose between the multiple PBE’s previously outlined. For a PBE to satisfy the intuitive criterion there must exist no deviation for any type of woman such that the best response of the dude leads to the woman strictly preferring a deviation from the originally chosen strategy.

Let’s explain why the all silent strategy does not satisfy this requirement. Imagine a deviation for the dirty player to calling. If the woman now calls, the best response for the dude is to throw to her, which yields a payoff of 2 for the woman, which is strictly greater than 0. So, the woman prefers this deviation and the intuitive criterion is not satisfied. However, the all call strategy passes this criterion. Imagine a deviation to silence for the dirty player. Then there is no best response for the dude since the payoffs are automatically 0 and 0. Since , the woman doesn’t prefer the deviation. Similarly, a deviation to silence for the scrub yields 0 instead of 1, which is not preferred either. Thus, the all call strategy satisfies the intuitive criterion. In effect, when we refine the set of equilibria in this way, we have both types of women calling for the disc and the dude making the throw… Sounds like a pretty good equilibrium to me!10

d. Recap of “throw it to the girl”

We have used this “throw it to the girl” set-up and its corresponding extensive form in order to discuss dynamic signaling games, solving for perfect bayesian equilibrium, and refining the set of equilibria using the intuitive criterion.

Hard cap is on!11

There are endless ways to extend or reform these games in the world of game theoretic concepts. My formulations for “calling lines” and “throw it to the girl” are simple by design in order that they lend themselves to discussing some subset of useful concepts. However, despite the simplicity of the model builds, I’m happy to be able to arrive at conclusions that involve social behaviors as complex as gender dynamics… For example, next time, instead of yelling “throw it to the girl!” from the sideline, you can always shout: “assuming a gift-giving game payoff structure, it is a perfect bayesian equilibrium satisfying the intuitive criterion for you to throw to open women when they call for it!” No worries – if they don’t understand, you can always womansplain the concept during the next time-out.

Code

Check out this Github repo for all tex files necessary for reproducing the tables, tree diagrams, and solution write-ups!

-

The good news is that since I’m pretty sure some nontrivial percentage of ultimate players have studied math, I don’t have to worry too much about this discussion being for some empty intersection of individuals. ↩︎

-

Comments on how to improve this are very welcomed. For this introductory context, I feel these payoffs suffice since it allows me to get into the prisoner’s dilemma and some useful simple equilibrium concepts. ↩︎

-

These requirements render the game a non-cooperative one. Prisoner’s dilemma terminology is often used for contexts that in fact would be better categorized as cooperative games such as Stag hunt. In the Stag hunt (or cooperative game) payoff matrix, the inequality relationship would instead be:

[the payoff to a player who "cooperates" while the other "cooperates"] > [the payoff to a player who "defects" while the other "cooperates"] >= [the payoff to a player who "defects" while the other "defects"] > [the payoff to a player who "cooperates" while the other "defects"]↩︎ -

Quick refresher as to how to find these marked best responses: Imagine team 1 plays a weak line, then the payoffs to team 2 are either 1 (if play weak) or 2 (if play strong). Since , team 2 will play strong. Imagine team 1 plays a strong line, then the payoffs to team 2 are either -2 (if plays weak) or -1 (if plays strong). Since , team 2 will play strong. The same logic then applies to team 1 since the game is symmetric. ↩︎

-

For a more complete discussion of repeated games and cooperation, check out these slides. ↩︎

-

See here for an article on this exact subject that a fellow female frisbee friend recently shared! ↩︎

-

Yeah, frisbee vernacular. Let’s go. ↩︎

-

This was an arbitrary choice – open to edits on this. ↩︎

-

Thank you to Dr. Chiu Yu Ko who has an incredible set of TikZ Templates openly available – Here is the signaling game one that I built off of. ↩︎

-

More generally, this will be the case as long as the nature a priori probabilities have the probability of the woman being dirty as 0.5 or greater. ↩︎

-

In frisbee parlance, it’s time to wrap this all up. ↩︎