Intro

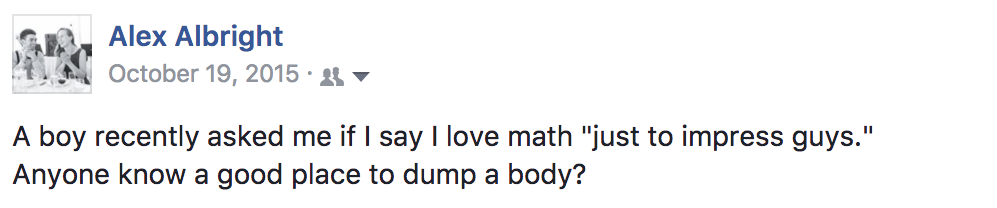

Hello world, I am now a G2 in economics PhD-land. This means I have moved up in the academic hierarchy; I now reign over my very own cube, and I am taking classes in my fields of interest. For me that means: Social Economics, Behavioral Economics, and Market Design. That also means I am coming across a lot of models, concepts, results that I want to tell you (whoever you are!) about. So, please humor me in this quasi-academic-paper-story-time… Today’s topic: Coate and Loury (1993)’s model of self-fulfilling negative stereotypes, a model presented in Social Economics.

Once upon a time…

There was a woman who liked math. She wanted to be a data scientist at a big tech company and finally don the company hoodie uniform she kept seeing on Caltrain. Though she had been a real ace at cryptography and tiling theory in college (this is the ultimate clue that this woman is not based on yours truly), she hadn’t been exposed to any coding during her studies. She was considering taking online courses to learn R or Python, or maybe one of those bootcamps… they also have hoodies, she thought.

She figured that learning to code and building a portfolio of work on Github would be a meaningful signal to potential employers as to her future quality as an employee. But, of course, she knew that there are real, significant costs to investing in developing these skills… Meanwhile, in a land far, far away – in an office ripe with ping pong tables – individuals at a tech company were engaged in decisions of their own: the very hiring decisions that our math-adoring woman was taking into account.

So, did this woman invest in coding skills and become a qualified candidate? Moreover, did she get hired? Well, this is going to take some equations to figure out, but, thankfully, this fictional woman as well as your non-fictitious female author dig that sort of thing.

Model Mechanics of “Self-Fulfilling Negative Stereotypes”

Let’s talk a little about this world that our story takes place in. Well, it’s 1993 and we are transported onto the pages of the American Economic Review. In the beginning Coate and Loury created the workers and the employers. And Coate and Loury said, “Let there be gender,” and there was gender. Each worker is also assigned a cost of investment, $c$. Given the knowledge of personal investment cost and one’s own gender, the worker makes the binary decision between whether or not to invest in coding skills and thus become qualified for some amorphous tech job. Based on the investment decision, nature endows each worker with an informative signal, $s$, which employers then can observe. Employers, armed with knowledge of an applicant’s gender and signal, make a yes-no hiring decision.

Of course, applicants want to be hired and employers want to hire qualified applicants. As such, payoffs are as follows:

Applicants receive:

$w$if they are hired and did not invest$w-c$if they are hired and invested$0$if they are not hired and did not invest$-c$if they are not hired and invested

On the tech company side, a firm receives (in $ terms):

$q$if they hire a qualified worker$u$if they hire an unqualified worker$0$if they choose not to hire

Note importantly that employers do not observe whether or not an applicant is qualified. They just observe the signals distributed by nature. (The signals are informative and we have the monotone likelihood ratio property… meaning the better the signal the more likely the candidate is qualified and the lower the signal the more likely the candidate isn’t qualified.) Moreover, gender doesn’t enter the signal distribution at all. Nor does it influence the cost of investment that nature distributes. Nor the payoffs to the employer (as would be the case in the Beckerian model of taste-based discrimination). But… it will still manage to come into play!

How does gender come into play then, you ask? In equilibrium! See, in equilibrium, agents seek to maximize expected payoffs. And, expected payoffs depend on the tech company’s prior probability that the worker is qualified, $p$. Tech companies then use $p$ and observed signal $s$ to update their beliefs via Bayes’ Rule. So, the company now has some posterior probability, $B(s,p)$, that is a function of $p$ and $s$. The company’s expected payoff is thus $B(s,p)(q) - (1-B(s,p))(-u)$ since that is the product of the probability of the candidate’s being qualified and the gain from hiring a qualified candidate less the product of the candidate’s being unqualified and the penalty to hiring an unqualified candidate. The tech company will hire a candidate if that difference is greater than or equal to $0$.

In effect, the company decision is then characterized by a threshold rule such that they accept applicants with signal greater than or equal to $s^*(p)$ such that the expected payoff equals 0. Now, note that this $s^*$ is a function of $p$. That’s because if $p$ changes in the equation $B(s,p)(q) - (1-B(s,p))(-u)=0$, there’s now a new $s$ that makes it hold with equality. As such, tech companies hold different genders to different standards in this model. Namely, it turns out that $s^*(p)$ is decreasing in $p$, which means intuitively that the more pessimistic employer beliefs are about a particular group, the harder the standards that group faces.

So, let’s say, fictionally that tech companies thought, hmmm I don’t know, “the distribution of preferences and abilities of men and women differ in part due to biological causes and that these differences may explain why we don’t see equal representation of women in tech and leadership” (Source: a certain memo). Such a statement about differential abilities yields a lower $p$ for women than for men. In this model. that means women will face higher standards for employment.

Now, what does that mean for our math-smitten woman who wanted to decide whether to learn to code or not? In this model, workers anticipate standards. Applicants know that if they invest, they receive an amount:

(probability of being above standard as a qualified applicant)(w) + (probability of falling below standard as a qualified applicant)(0) - c

If they don’t invest, they receive:

(probability of being above standard as an unqualified applicant)(w) + (probability of falling below standard as an unqualified applicant)(0)

Workers invest only if the former is greater than or equal to the latter. If the model’s standard is higher for women than men, as the tech company’s prior probability that women are qualified is smaller than it is for men, then the threshold for investing for women will be higher than it is for men.

So, if in this model-world, that tech company (with all the ping pong balls) is one of a ton of identical tech companies that believe, for some reason or another, that women are less likely to be qualified than men for jobs in the industry, women are then induced to meet a higher standard for hire. That higher standard, in effect, is internalized by women who then don’t invest as much. In the words of the original paper, “In this way, the employers’ initial negative beliefs are confirmed.”

The equilibrium, therefore, induces worker behavior that legitimizes the original beliefs of the tech companies. This is a case of statistical discrimination that is self-fulfilling. It is an equilibrium that is meant to be broken, but it is incredibly tricky to do so. Once workers have been induced to validate employer beliefs, then those beliefs are correct… and, how do you correct them?

I certainly don’t have the answer. But, on my end, I’ll keep studying models and attempting to shift some peoples’ priors…

Oh, and my fictional female math-enthusiast will be endowed with as many tech hoodies as she desires. In my imagination, she has escaped the world of this model and found a tech company with a more favorable prior. A girl can dream…

Endnote

This post adapts Coate and Loury (1993) to the case of women in tech in order to demonstrate and summarize the model’s dynamics of self-fulfilling negative stereotypes. Discussion and lecture in Social Economics class informed this post. Note that these ideas need not be focused on gender and tech. They are applicable to many other realms, including negative racial group stereotypes and impacts on a range of outcomes, from mortgage decisions to even police brutality.