Newsletter e-mails are often artifacts of faded interests or ancient online shopping endeavors. They can be nostalgia-inducing – virtual time capsules set in motion by your past self at $t-2$, and egged on by your past self at $t-1$. Remember that free comedy show, that desk lamp purchase (the one that looks Pixar-esque), that political campaign… oof, actually let’s scratch that last one. But, without careful care, newsletters breed like rabbits and mercilessly crowd inboxes. If you wish to escape the onslaught of red notification bubbles, these e-mails are a sworn enemy whose defeat is an ever-elusive ambition.

However, there is a newsletter whose appearance in my inbox I perpetually welcome with giddy curiosity. That is, Jeremy Singer-Vine’s “Data is Plural.” Every week features a new batch of datasets for your consideration. One dataset in particular caught my eye in the 2017.07.19 edition:

UN General Debate speeches. Each September, the United Nations gathers for its annual General Assembly. Among the activities: the General Debate, a series of speeches delivered by the UN’s nearly 200 member states. The statements provide “an invaluable and, largely untapped, source of information on governments’ policy preferences across a wide range of issues over time,” write a trio of researchers who, earlier this year, published the UN General Debate Corpus – a dataset containing the transcripts of 7,701 speeches from 1970 to 2016.

The Corpus explains that these statements are “akin to the annual legislative state-of-the-union addresses in domestic politics.” As such, they provide a valuable resource for understanding international governments’ “perspective[s] on the major issues in world politics.” Now, I have been interested in playing around with text mining in R for a while. So a rich dataset of international speeches seems like a natural application of basic term frequency and sentiment analysis methods. As I am interested in comparing countries to one another, I need to select a subset of the hundreds to study. Given their special status, I focus exclusively on the five UN Security council countries: US, Britain, France, China, and Russia.1 Following in the typed footsteps of great code tutorials, I perform two types of analyses – a term frequency analysis and a sentiment analysis – to discuss the thousands of words that were pieced together to form these countries’ speeches.

Term Frequency Analysis

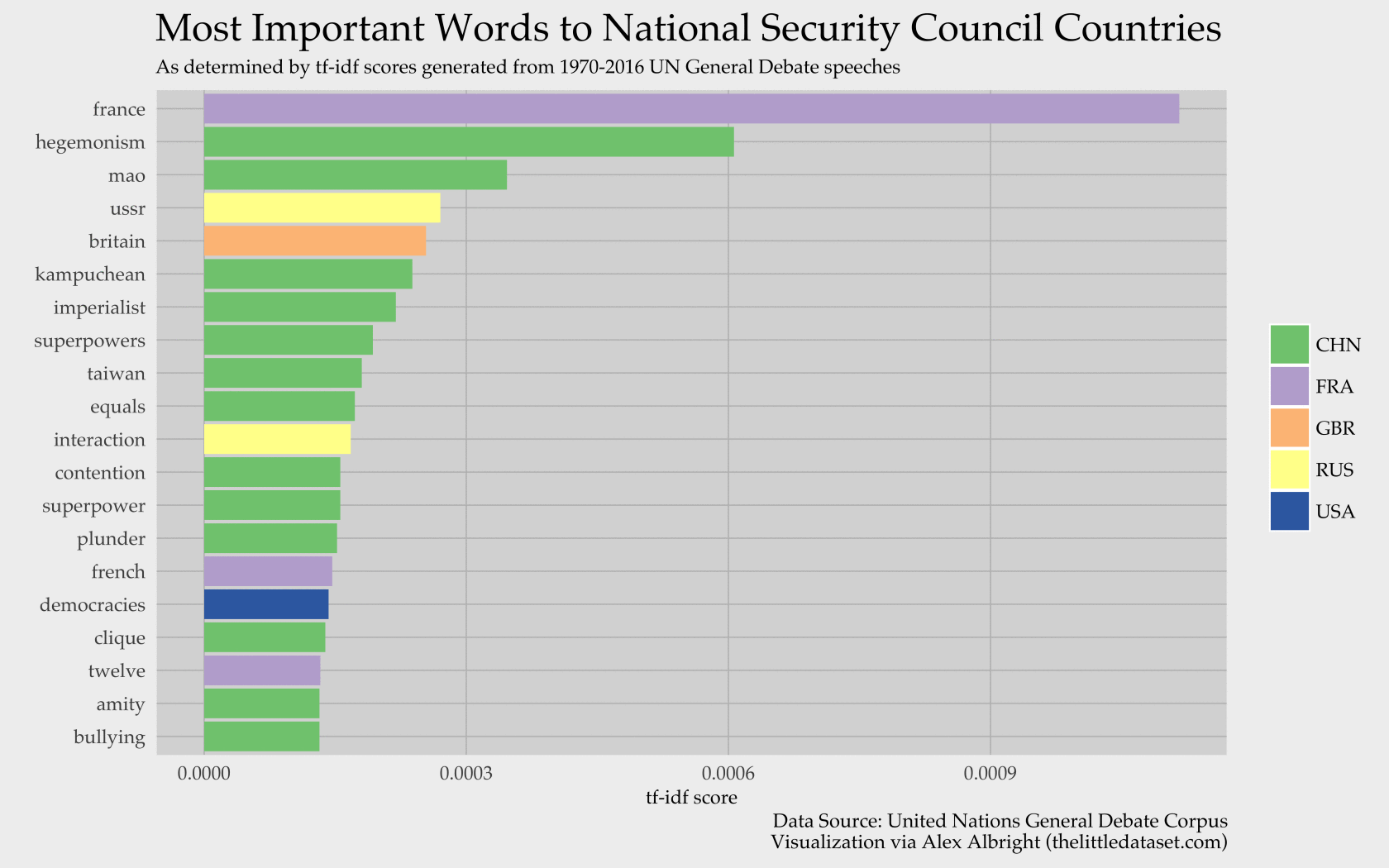

Term frequency analysis has been used in contexts ranging from studying Seinfeld to studying the field of 2016 GOP candidates. A popular metric for such analyses is tf-idf, which is a score of relative term importance. Applied to my context, the metric reveals words that are frequently used by one country but infrequently used by the other four. In more general terms, “[t]he tf-idf value increases proportionally to the number of times a word appears in the document, but is often offset by the frequency of the word in the corpus, which helps to adjust for the fact that some words appear more frequently in general.”2 In short, tf-idf picks out important words for our countries of interest. The 20 words with the highest tf-idf scores are illustrated below:

China is responsible for 13 of the 20 words. Perhaps this means that China boasts the most unique vocabulary of the Security Council.3 Now, if instead we want to see the top 5 words for each country – to learn something about their differing focuses – we obtain the results below:

As an American, I am not at all surprised by the picture of my country as one of democratic, god-loving, dream-having entrepreneurs who have a lot to say about Saddam Hussein. Other insights to draw from this picture are: China is troubled by Western superpower countries influencing (“imperialist”) or dominating (“hegemonism”) others, Russia’s old status as the USSR involved lots of name checks to leader Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, and Britain and France like to talk in the third-person.

Sentiment Analysis

In the world of sentiment analysis, I am primarily curious about which countries give the most and least positive speeches. To figure this out, I calculate positivity scores for each country according to the three sentiment dictionaries, as summarized by the UC Business Analytics R Programming Guide:

The

nrclexicon categorizes words in a binary fashion (“yes”/“no”) into categories of positive, negative, anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, and trust. Thebinglexicon categorizes words in a binary fashion into positive and negative categories. TheAFINNlexicon assigns words with a score that runs between -5 and 5, with negative scores indicating negative sentiment and positive scores indicating positive sentiment.

Therefore, for the nrc and bing lexicons, my generated positivity scores will reflect the number of positive words less the number of negative words. Meanwhile, the AFINN lexicon positivity score will reflect the sum total of all scores (as words have positive scores if they possess positive sentiment and negative scores if they possess negative sentiment). Comparing these three positivity scores across the five Security Council countries yields the following graphic:

The three methods yield different outcomes: AFINN and bing conclude that China is the most positive country, followed by the US; meanwhile, the nrc identifies the US as the most positive country, with China in fourth place. And, despite all that disagreement, at least everyone can agree that the UK is the least positive! (How else do we explain “Peep Show”?)

Out of curiosity, I also calculate the nrc lexicon word counts for anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, and trust. I then divide the sentiment counts by total numbers of words attributed to each country so as to present the percentage of words with some emotional range rather than the absolute levels for that range. The results are displayed below in stacked and unstacked formats.

According to this analysis, the US is the most emotional country with over 30% of words associated with a NRC sentiment. China comes in second, followed by the UK, France, and Russia, in that order. However, all five are very close in terms of emotional word percentages so this ordering does not seem to be particularly striking or meaningful. Moreover, the specific range of emotions looks very similar country by country as well. Perhaps this is due to countries following some well-known framework of a General Debate Speech, or perhaps political speeches in general follow some tacit emotional script displaying this mix of emotions…

I wonder how such speeches compare to a novel or a newspaper article in terms of these lexicon scores. For instance, I’d imagine that the we’d observe more evidence of emotion in these speeches than in newspaper articles, as those are meant to be objective and clear4, while political speeches might pick out words specifically to elicit emotion. It would be fascinating to investigate how emotional words are wielded in political speeches or new forms of journalistic media, and how that has evolved over time.5 But, I will leave that work (for now) to people with more in their linguistics toolkit than a novice knowledge of super fun R packages.

Code

As per my updated workflow, I now conduct projects exclusively using R notebooks! So, here is the R notebook responsible for the creation of the included visuals. And, here is the associated Github repo with everything required to replicate the analysis.

Methods mimic those outlined by superheRos Julia Silge and David Robinson in their “Text Mining with R” book.

-

Of course, you could include many, many more countries of interest for this sort of investigation, but given the format of my desired visuals, five countries is a good cut-off. ↩︎

-

Let me know if you disagree with that interpretation. ↩︎

-

However, this is less true of new forms of evolving media. I.e., those that aim to further polarize the public… or, those that were aided by one of the Security Council countries to influence an election in another of the Security Council countries. (Yikes.) ↩︎

-

Quick hypothesis: fear is more present in the words that make up American media coverage and political discourse nowadays than it was a year ago. ↩︎