This piece was conceptualized jointly and co-written with my insightful colleagues Steph Kestelman, Kristen McCormack, and Isabel Harbaugh Macdonald.

Since shelter-in-place started, academic economists have changed how they do research (e.g., at home and not at the office or in the field), their research intensity and productivity,1 and even what they are researching. We haven’t experienced a pandemic and economic crisis of the current magnitude in our lifetimes, so there is both a lack of and need for evidence on how COVID-19 is impacting lives and the global economic system. Researching questions related to COVID-19 is of obvious public importance and there are significant work-based incentives to produce and publicize related research quickly.2

Who tends to be first to comment/present on these new topics? In our department, an early-stage seminar on the economics of COVID-19 features talks by faculty and grad students. A few of us have been surprised by the dearth of female speakers in the seminar. Only 1 of the 12 student presenters (April 9 - May 14) was a woman.3 Only 2 of the 12 student projects had any female co-authors. On the whole, fewer than 10% of authors across the papers presented in the COVID-19 seminar were women.4 These numbers are striking, but they don’t tell the whole story – are women in our department simply not pursuing research questions related to COVID-19, or is something else going on?

There has been a lot of discussion about how COVID-19 might be impacting women and men differently in their research productivity. Journal editors have pointed out that submissions are up… but only for men, not women.5 Some early data from professional working paper series shows that women are putting out fewer papers on COVID-19 – “women constitute only 12% of the total number of authors working on COVID-19”.6 The reasons behind this trend and whether it will be long-lasting, however, remain unclear.7

After observing the striking lack of women in the grad student COVID-19 presentations, we wanted to figure out whether women in our department were studying the COVID-19 crisis at lower rates than men, or if they just haven’t participated in the seminar yet8 and what mechanisms could be driving these differences.

Survey provides insight into possible mechanisms

To bring up these questions informally is difficult at the moment since we aren’t around each other physically. We also figured there is a lot going on right now in people’s time allocation that we don’t know; everyone’s workflow is more invisible than usual. So, we made a survey that we sent out to our economics and public policy programs to get a sense of time use changes (for department benefit) and then also included a few questions about COVID-19 work to try to dig into “who is doing COVID-19 research?” and “who is already talking about this research?”. We collected limited demographic characteristics9 to minimize the risk that individuals in our departments could be easily identified. We received 114 responses, which is approximately 50% of the total graduate student population in economics-based PhD programs (excluding those graduating).

Before examining survey responses, we arrived at a few possible explanations for the observed disparities:

-

Women are less likely to take-up COVID-19 topics

- This could be due to differences in underlying fields (people in development not having access to COVID-19 data, macro theorists being able to work on models with low barriers to entry) or differences in risk aversion (risky to switch to a new topic so quickly, especially if it’s unrelated or only somewhat related to previous work)

-

Conditional on similar COVID-19 project rates, women are making less progress on research than men

- This could be due to women losing more research time to other aspects of life or women working with fewer coauthors

-

Conditional on similar COVID-19 project rates and similar research time, men are more comfortable presenting this early-stage work

- This could be due to confidence gaps or gaps in working with faculty members (who might encourage presentations or legitimize the presentation in a student’s mind)

We now get into how the survey results jibe with these different possible explanations.

Key results show women do have COVID-19 projects, but men are quicker to present

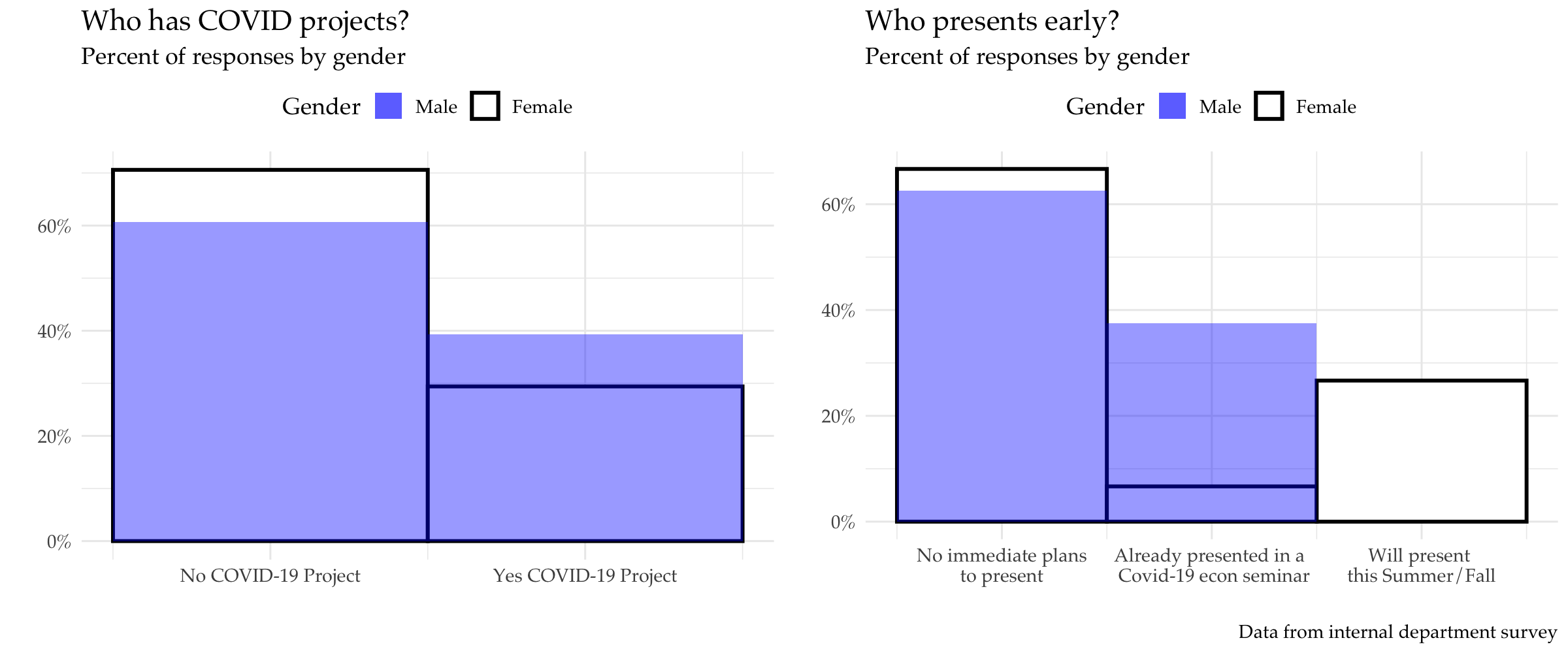

For one, our survey shows that 40% of students with a COVID-19 project are women while 45% of our respondents are women. So, the extensive margin (“having a COVID-19 project”) doesn’t explain the large gender difference in grad student presentation rates.

Given that 40% of those with a COVID-19 project are women but only 1 out of 12 student presenters were women, the main difference must be in the decision to present quickly conditional on having a project.

The above visual shows that this is exactly what’s going on. The left panel shows the percent of men and women who have a COVID-19 project and the right panel shows the presentation plans by gender among those with a project. What is really striking is that while men are only slightly more likely than women to have a COVID-19 project, all men with presentation ambitions have already presented! By contrast, most women with presentation ambitions are planning to present for the first time in the Summer/Fall. This is good news for those of us reading developing work on COVID-19 since it suggests that the gender skew may well reverse in the coming months, leading to a less jarring gender disparity once more presentations have happened. There is some concern, however, that any new work will have to refer back to those initial papers, which might make female-authored work look less du jour. Thinking about project impact (the “quality” margin) is outside the scope of our project.10

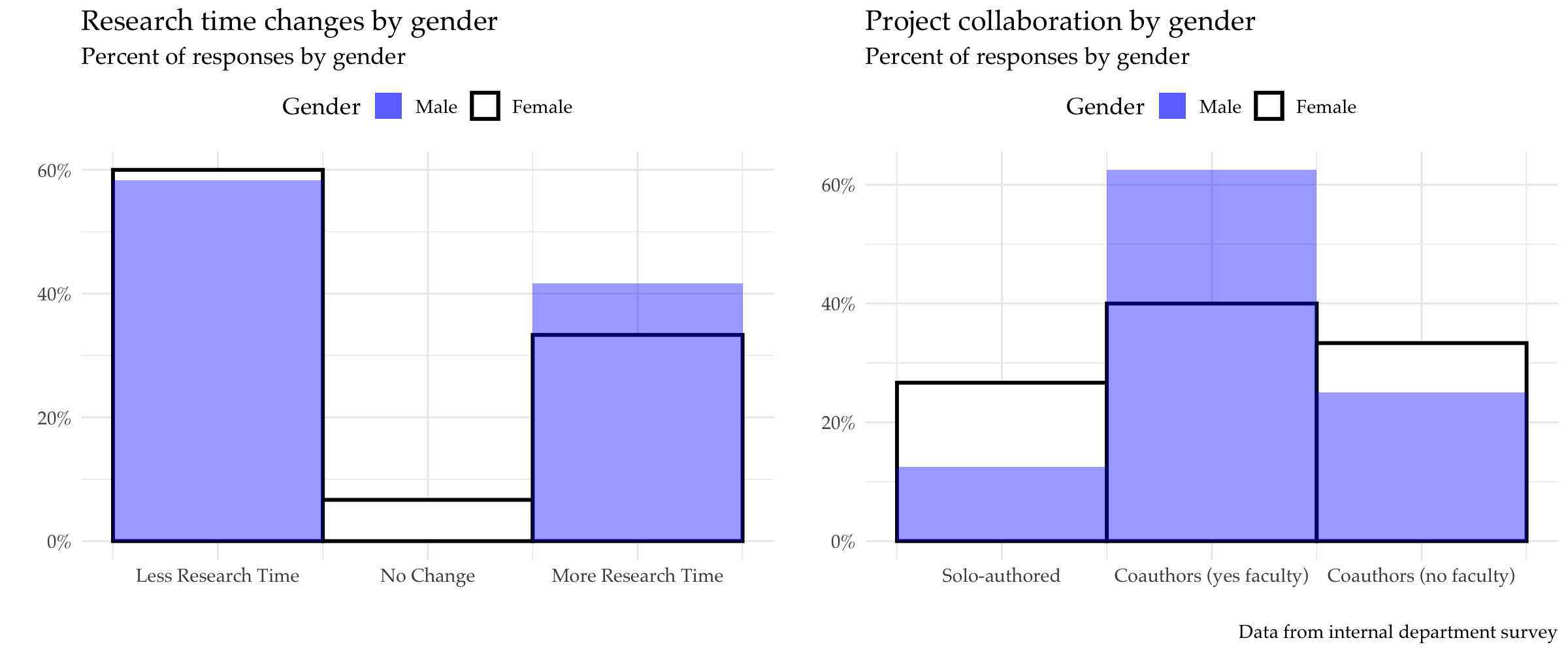

Why would there be this difference in speed to present by gender?11 Are women with COVID-19 projects experiencing greater losses in research time than men? Are they less likely to have co-authors who can accelerate the pace of the project? Are they less likely to co-author with faculty who may provide resources or reassurance about the readiness of the project?

To address these questions, we present the above graph. The left panel above shows how research time changed between February 2020 (before we left campus due to COVID-19) and April 2020 (after we left campus) for those with COVID-19 projects. The right panel shows the likelihood of different collaboration types for those with COVID-19 projects. Men with COVID-19 projects are more likely to have experienced gains in their research time, but this channel isn’t as striking as the differences in collaboration (see the right panel above). This panel demonstrates that women are less likely to be collaborating on COVID-19 projects. This can help explain some of the lag in presentation time. Moreover, even when women are collaborating with others, women are less likely to collaborate with academic faculty. It’s possible that co-authoring with faculty makes one more likely to quickly present given the confidence boost and sense of assurance that the work is attributable to faculty as well.12

Conclusion: men have been quicker out of the gate but gender disparities may lessen with time

Despite the visible early skew of COVID-19 projects towards male grad students, there are many women working on COVID-19 projects as well. Men appear to have just been quicker out of the gate to present their research, which is likely partially driven by higher rates of co-authoring, especially with faculty.

Based on our survey evidence, it’s likely that we will see a flow of COVID-19 projects with female co-authors in the future months that will balance out the early gender disparities (perhaps this will also be the case with the various paper series too?). Our evidence suggests that for grad students, men are quicker to present than women, even though women have chosen to pursue COVID-19-related projects at similar rates.

-

Journal editors report that submissions have spiked even though many academics are getting only a few hours of work in due to home-schooling. Moving online and sheltering in place has had heterogeneous effects on people’s work-life balance based on their situation. The Guardian wrote a piece on this. ↩︎

-

Putting research out quickly can help guide policy in an uncertain time. The opportunities for COVID-19 funding and quick publication (short articles for the Journal of Urban Economics and the Journal of Public Economics) offer large incentives for COVID-19-related projects. ↩︎

-

For institutional context, we estimate about 30-40% of those in our economics-related programs are women. ↩︎

-

Calculations performed by the authors. ↩︎

-

This Higher Ed article summarizes statistics on journal submissions in political science and some of the physical sciences. Shelly Lundberg asked her Twitter followers if they had any data on submissions to economics journals, and some responses can be found in her thread. This post by Anne Sofie Beck Knudsen looks at the gender of NBER Working Paper (NBER WP) authors. Similarly, Raymundo Campos Vasquez looked at the gender of authors of NBER WP and VoxEU working papers. ↩︎

-

There are a few anecdotes online about how women have been less represented in broad (beyond econ) discussions on COVID-19. Here’s a thread with some documentation on a university publicizing 8 male and 0 non-male perspectives on COVID-19. ↩︎

-

One Twitter user wrote the following comment on the thread about the lack of female authors on COVID-19 working papers: “maybe women are less comfortable rushing out with half-baked crap before the evidence has been properly analyzed?” ↩︎

-

We also wanted to see how COVID-19 has impacted grad student time use on the whole for the sake of our department, but we don’t get into those results here since they are for internal use. ↩︎

-

We collected gender, a coarse PhD year indicator (<=G2 or >=G3), and general area of study. We purposely did not request information on race for privacy reasons – the very small number of BIPOC students in our programs mean that some people would be easily identifiable from their survey responses. That fact as well as the fact that less than 0.5 percent of economics PhD’s are awarded to Black women should make clear that economics has a large racial diversity problem. If you’d like to learn more about this topic, we suggest engaging with and learning from the Sadie Collective. ↩︎

-

Erin Hengel has some interesting work on how women are held to higher publication standards. ↩︎

-

Women in our sample are also slightly more likely to have no plans to present, but given our small sample, it’s not worth putting much weight on that channel. ↩︎

-

In her 2019 paper, Heather Sarsons shows that women receive little to no credit for work done with more senior coauthors, which might partially explain the lower rates of collaboration between female students and faculty (there are few female faculty at Harvard). ↩︎